Antipsychotics associated with increased risk of pneumonia

By Debbie Andalo

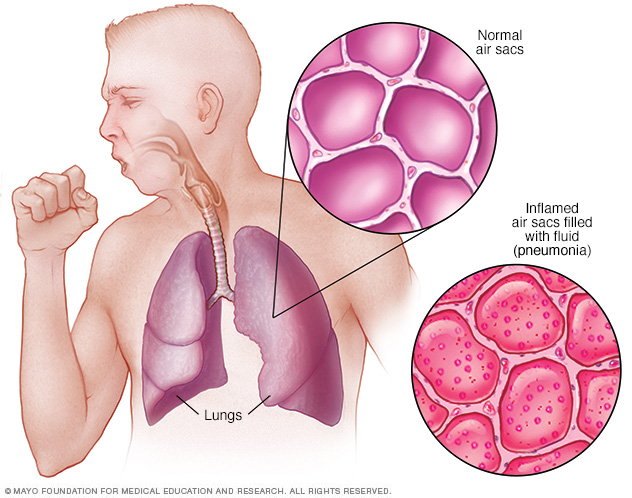

Use of antipsychotic drugs is associated with a higher risk of pneumonia in patients of all ages with or without Alzheimer’s disease, study finds.

The use of antipsychotic drugs in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) doubles their risk of pneumonia, while pneumonia risk in patients without AD who take antipsychotics is more than three-fold, according to research from Finland.

The researchers, who report their findings in Chest, warn that the real risk of pneumonia may be even higher because their study only included cases of pneumonia that led to a hospital stay or patient death.

“Risk-benefit balance should be considered when antipsychotics are prescribed,” the researchers recommend. “Especially old persons who initiate antipsychotic treatment should be closely monitored.”

The team concludes that antipsychotic use is linked to higher pneumonia risk regardless of age, duration of treatment, choice of medication or comorbidities.

CLICK HERE for more resources on Psychiatric/Mental Health

The observational study included 60,584 patients diagnosed with AD who were aged on average 80.1 years and of whom 65.2% were women.

The researchers examined patients’ use of antipsychotics and whether they had a diagnosis of pneumonia that led to hospital admission or death, comparing them with a similar group of patients who did not have AD but were also prescribed antipsychotics.

They found that antipsychotic use was associated with increased pneumonia risk in both groups of patients. There was no difference in risk linked to which antipsychotic was prescribed.

In the AD cohort, antipsychotic users had two-fold relative risk of pneumonia (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 2.01, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.90-2.13).

The association was stronger in the non-AD cohort (adjusted HR 3.43, CI 2.99-3.93). In both cohorts, antipsychotic use was consistently associated with higher risk of pneumonia in all age groups.

When the pneumonia risk among users was compared with treatment duration, patients with the shortest duration of use had the highest relative risk increase; the risk was not attenuated in long-term use.

The age-adjusted pneumonia incidence in non-users of AD cohort was 4.83 per 100 person years. The incidence was 13.66 pneumonias per 100 person years in patients who had taken antipsychotics for 7–12 months and 5.30 pneumonias per 100 person years in patients who had taken them for more than one year.

Derek Taylor, chair of the United Kingdom Clinical Pharmacy Association’s Care of the Elderly Group, says: “The results of this study reinforce the existing concern over an increased risk of pneumonia in all patients prescribed an antipsychotic agent.”

Taylor, assistant director of pharmacy in governance & risk at the Royal Liverpool & Broadgreen University Hospitals NHS Trust, says the results of the study suggest that the increased risk of pneumonia appears soon after starting antipsychotic therapy and does not seem to decrease significantly with time in longer-term treatment.

“This would indicate that clinicians should be aware of this increased risk throughout a persons’ antipsychotic treatment course,” he says.

“I do not believe that the results of this study will dramatically alter the prescribing or choice of antipsychotics in patients with AD. However, it does reinforce the need for regular monitoring of patients on both short and longer-term treatment.”

References:

Tolppanen A-M, Koponen M, Tanskanen A et al. Antipsychotic use and risk of hospitalisation or death due to pneumonia in persons with and without Alzheimer’s disease. Chest 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.06.004

Citation: The Pharmaceutical Journal, PJ September 2016 online, online | DOI: 10.1211/PJ.2016.20201657